The Bay Area legal community has extra cause for celebration this Black History Month as we celebrate the inauguration of the first Black woman Vice President, Kamala Harris, a member of our own legal community. As we celebrate this historic milestone, we would like to highlight one of the amazing Black women who paved the way. As Vice President Harris has said, “I stand on the shoulders of giants”.

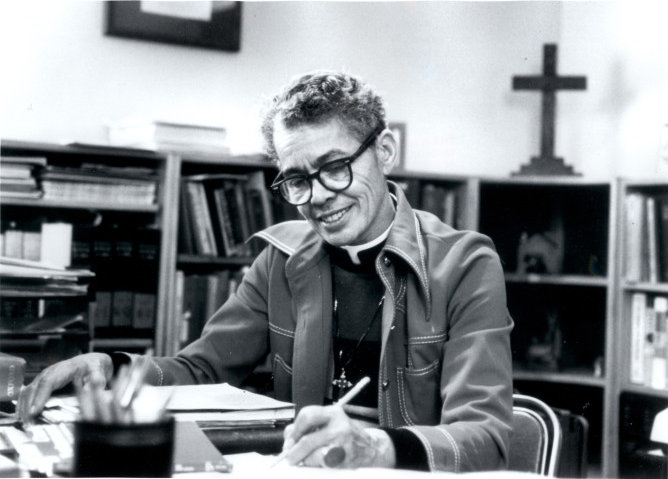

Pauli Murray easily qualifies as one of these giants. I first heard of Pauli Murray a few years ago when my alma mater, Yale College, named one of our new residential colleges in her honor. Murray was an accomplished Black queer civil rights leader, attorney, feminist, author and religious leader.

Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland on November 20, 1910, the fourth of six children. Murray earned degrees from Hunter College, Howard Law, UC Berkeley Law and Yale Law. Despite facing significant discrimination on the basis of both her race and gender, Murray lived an influential life and had a storied career. President John F. Kennedy appointed Murray to serve on the Committee on Civil and Political Rights as a part of his Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. Murray also co-founded NOW (National Organization for Women) and served as a faculty member at Brandeis University, where she introduced African American studies and gender studies to the curriculum.

Murray also spent time litigating at Paul, Weiss, Rifkin, Wharton, and Garrison and in her mid-sixties became the first African-American woman in the United States ordained to the priesthood in the Episcopal Church. Murray authored Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII and Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy, proffering influential legal arguments challenging the legal foundations of systemic racial discrimination. Murray explained, “Black women, historically, have been doubly victimized by the twin immoralities of Jim Crow and Jane Crow…Black women, faced with these dual barriers, have often found that sex bias is more formidable than racial bias.” Murray’s ideas impacted Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s legal arguments in the seminal case of Reed v. Reed and Thurgood Marshall’s arguments in Brown v. Board of Education.

Before the word “intersectionality” even existed, Murray brought her full self to her career and paved the way for other women of color to follow her example. In the later part of her life, she incorporated her lived experiences into her sermons as an Episcopal priest. In one sermon she preached:

“It was my destiny to be the descendant of slave owners as well as slaves, to be of mixed ancestry, to be biologically and psychologically integrated in a world where the separation of the races was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States as the fundamental law of our Southland. My entire life’s quest has been for spiritual integration, and this quest has led me ultimately to Christ, in whom there is no East or West, no North or South, no Black or White, no Red or Yellow, no Jew or Gentile, no Islam or Buddhist, no Baptist, Methodist, Episcopalian, or Roman Catholic, no Male or Female. There is no Black Christ, no White Christ, no Red Christ – although these images may have transitory cultural value. There is only Christ, the Spirit of Love.”

Murray did not see her religious faith and activism to be at odds with her rigorous legal education. Through coupling seemingly disparate parts of herself, she left a mark on society.

As we celebrate Black History Month, trailblazers like Murray remind us that we need to bring our authentic and full selves in order to effectively make change. As Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley says, “The people closest to the pain should be closest to the power.” Murray’s existence as a queer Black woman in America meant that she had to navigate various types of discrimination and experience varying degrees of pain. Yet, it was through this pain and her intellect and faith that she proffered arguments and contributed to the civil rights movement in a way that turned power structures on their head. One of Murray’s famous quotes is “Hope is a song in a weary throat.” The melody of Murray’s life still reverberates in the Black community in America and laid the foundation for the rise of the sopranos that we see in leaders like Vice President Harris that we celebrate today.

About the Author:

Antonio Ingram is a Justice & Diversity Center (JDC) 2011 scholarship recipient and attended Berkeley Law. He previously served as a federal judicial law clerk at both the district court and circuit court level and as Public Policy Fulbright Fellow in Malawi. He is currently a senior litigation associate at Boies Schiller Flexner in their San Francisco office.