The Nineteenth Amendment federally guaranteed women the right to vote on August 26, 1920: 100 years ago. On this occasion, celebration is warranted; but it is not enough.

The Nineteenth Amendment’s adoption followed over seven decades of continuous advocacy. The racial and class divisions that affected the movement seem all too familiar today. Yet, there are many things it did not change. Women of all races did not suddenly gain unimpeded access to the polls. Native American women were excluded from the franchise by the Snyder Act until 1924, Chinese American women were excluded by the Chinese Exclusion Act until 1943, and Black and Latina women were effectively excluded by poll taxes, literacy tests, voter purges, outright violence and intimidation, and other racist voter suppression tactics, some of which persist today. The Nineteenth Amendment also did not swing open the doors to power or eliminate sexism, racism, and classism. Women, and particularly BIPOC1 women, are still underrepresented in positions of power in government and business. But, the Nineteenth Amendment is an important milestone on our journey, and we can find inspiration in this history as we continue to seek universal voting rights and a more inclusive society.

Abolitionists Controversially Agree to Advocate for Women’s Suffrage

The Seneca Falls Convention in July 1848, often cited as the birth of the United States’ suffrage movement, was organized by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who began their collaboration while attending abolitionist events where women were not permitted to speak. Over a hundred participants, including Frederick Douglass, attended the convention, which resulted in the Declaration of Sentiments. Suffrage was the most controversial resolution at the convention, which also sought reforms in education, employment, church, and property rights. Nevertheless, the Declaration of Sentiments proudly echoed the language of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” In 1866, following the end of the Civil War, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Frederick Douglass formed the American Equal Rights Association to achieve this goal. Douglass would remain an advocate for women’s suffrage until his death, despite divisions within the movement.

Division Among Suffragists in the 1860s

The 1860s would see division among advocates for universal suffrage. Some women (among them, Anthony, Stanton, and Sojourner Truth) objected to the Fifteenth Amendment omitting women, while others (including Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Douglass) supported the Fifteenth Amendment, and urged women to be patient. Two rival associations formed: Stanton and Anthony established the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), while Stone and Blackwell established the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). NWSA took a national strategy, and addressed social, economic, and political issues beyond suffrage. NWSA’s newsletter exhorted women to “earn their own livelihood,” a radical idea at the time. Echoing their opposition to a Fifteenth Amendment that excluded women, NWSA also resorted to racist appeals. AWSA by contrast adopted a state by state strategy and was considered a more moderate organization, focused on achieving suffrage for women without challenging other Victorian norms. The two groups would reconcile in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Black, Indigenous, and Women of Color Advocate Amid Racism

Black women created a wide network of suffrage groups across the country. In the 1890s, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper led the American Association of Colored Youth, and, along with Harriet Tubman, Mary Church Terrell, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett, was a founding member of the National Association of Colored Women, whose motto was “lifting as we climb.” Terrell was one of the first Black women to earn a college degree, graduating in 1884 from Oberlin College. She advocated for women’s suffrage and greater equality for Black women. Wells-Barnett advocated internationally for the rights of Black women, and openly confronted white women who ignored lynching.

Zitkala-Sa, a Yankton Sioux writer and political activist, advocated for women’s rights at the same time that she advocated for Native American rights. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, who immigrated to the United states from China as a young child, became a young leader for Chinese American women in lower Manhattan. She also led a large suffrage march in New York on horseback as a teenager.

Despite white women’s racism, prominent Black women’s advocates continued to fight alongside them in national organizations. As is still too often the case, these Black women were often the only ones in the room. At the 11th National Women’s Rights Convention in 1866, Watkins Harper movingly declared: “We are all bound up in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on its weakest and feeblest of members without receiving the curse in its own soul.”

The Fifteenth Amendment

The Fifteenth Amendment declared: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Many assume the right to vote referenced in the Amendment lies elsewhere in the Constitution. But the text of the Constitution only mentions voting rights to delegate to the states the decision about who qualifies. (Article I, Section 2: “the electors in each state shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the state legislature.”)

Despite the omission of women from the Fifteenth Amendment, several women tried to vote after its passage, famously including Susan B. Anthony, who was arrested for voting in 1872. Another NWSA member, Virginia Minor, took her challenge to the Supreme Court of the United States, arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote because it was a “privilege or immunity” guaranteed to all citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment. In the 1874 decision Minor v. Happersett, the Supreme Court rejected Minor’s argument. Because the Constitution gave states the right to determine eligibility to vote, it was not a “privilege or immunity” of a citizen.

Suffragists Modernized Political Activism

Women’s suffrage advocates used and built on the advocacy skills they had learned as abolitionists and prohibitionists. They also borrowed from British suffragists. Their public advocacy efforts, which started with meetings and conventions, came to include marches, parades, rallies, commemorative pins and stamps, fliers, and independent newspapers. In 1913, a group marched from New York to Washington, a journey of over 250 miles. During the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession, occurring in Washington the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, white leaders of NAWSA told black suffragists, including Ida B. Wells-Barnett, to walk at the back of the parade. She refused.

In 1917, women led by Alice Paul, who became known for her more radical methods, formed a “silent sentinel” in front of the White House. The sentinels allowed their banners to speak for them. At that time, picketing the White House was unheard of, and the banners were also seen as aggressive, pointing out the hypocrisy of the United States supporting self-determination abroad, when denying women the vote domestically. Some attacked these tactics as unpatriotic once the United States joined World War I, and in June, women began receiving tickets for “obstructing the sidewalk.” Things only escalated from there. Paul went on a hunger strike in the D.C. Jail and was force-fed. On November 14, 1917, thirty-three of the silent sentinels were arrested, beaten, and tortured. The suffragists dubbed this the “Night of Terror,” and publicized their treatment, passing out pins with jail bars on them to gain further public support.

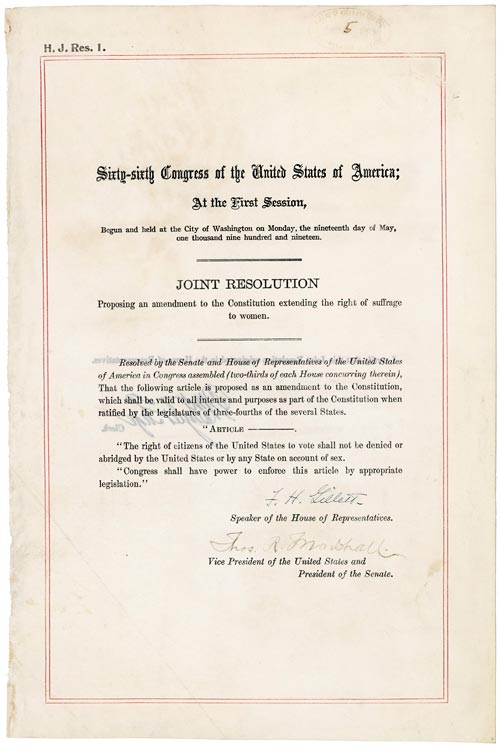

The Amendment

On June 4, 1919, the Senate finally passed the “Anthony Amendment.” But it remained to be ratified by three-fourths of the states. By that time, all of the Rocky Mountain West, and a few other states had granted women full voting rights. California had adopted women’s suffrage in 1911, although the referendum was decided by only 3,587 votes. Women’s suffrage had not yet taken hold in the following states: Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia. Thus, women had to fight for ratification in states where they could not vote. The Tennessee state legislature would be the 36th and final vote ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment. The legislature was split evenly down the middle, and twenty-four-year-old legislator Harry T. Burn cast the final vote, after famously receiving a letter from his mother that he should “be a good boy” and support the amendment.

Moving Forward

Voting rights were just the beginning for the suffragists of the 1920s. They hoped the Equal Rights Amendment would pass quickly. Although proposed in 1923, it would not pass until 1972, and was not ratified before its constitutional deadline, despite an extension. In January of this year, Virginia became the 38th State to ratify the Amendment. Whether the ratification has the effect of amending the constitution will likely be decided by the Supreme Court. In the meantime, women continue to use the political advocacy tools of our foremothers, and build on them to protect all of our rights.

About the Author:

Rebecca A. Bers is a Deputy City Attorney in San Francisco, where she regularly litigates in state and federal court. She serves as Secretary on the Executive Committee of the Bar Association’s Litigation Section, and on the Communications and Programs Committee for the Bar Association’s Women’s Impact Network – No Glass Ceiling 2.0 Committee.

1 BIPOC is an acronym for “Black, Indigenous, and People of Color” that has gained popularity recently. I use it to be inclusive and avoid the erasure of the different experiences of Black and Indigenous people.

0 comments on “Path to 19th Amendment Offers Lessons for Today”