This past March, Republican Senator Dean Heller of Nevada made waves when he predicted that Justice Anthony Kennedy would retire this summer. That may or may not happen—but if Justice Kennedy has decided to retire, it is unlikely he is feeding inside information about it to the senior senator from Nevada.

This past March, Republican Senator Dean Heller of Nevada made waves when he predicted that Justice Anthony Kennedy would retire this summer. That may or may not happen—but if Justice Kennedy has decided to retire, it is unlikely he is feeding inside information about it to the senior senator from Nevada.

But stop and ponder the broader context of Senator Heller’s remarks. He was observing that Republicans face an uphill climb in the 2018 election because the Republican base is not motivated to turn out—but that the prospect of a new Supreme Court Justice might change that. Think about that. The U.S. Senate is the most powerful legislative body in the world, and control of the chamber might hinge on the outcome of Senator Heller’s re-election race. And the most critical issue on which the senator thinks the race could turn is not some pressing issue of domestic or foreign policy—not the economy, not taxes, not education or the environment, not Iran or North Korea. No, the single most important question facing the country is who should replace Justice Kennedy on the Supreme Court. And the sad thing is, Senator Heller may be right.

The Politicization of the Judiciary

It is time to face reality: the centrality of the Supreme Court and the federal judiciary in politics is dangerous, it is undermining American democracy, and it is on track to get much worse.

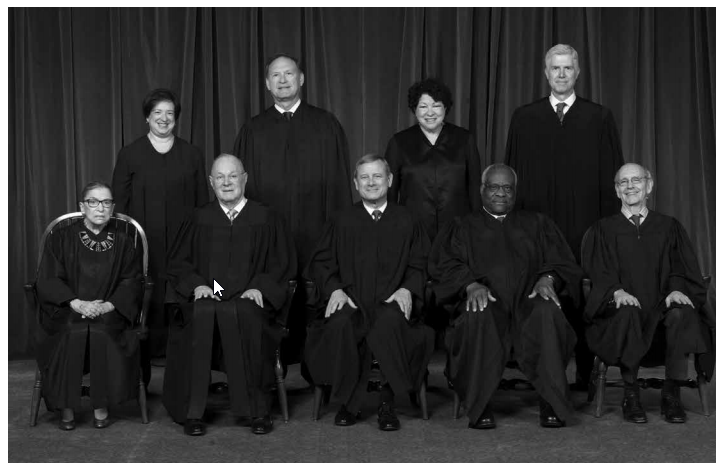

It’s no secret that the Supreme Court nomination and confirmation process, like everything else in Washington, has become more polarized in recent years. But the speed and magnitude of the change are breathtaking. A generation ago, Justices Scalia and Ginsburg were confirmed by overwhelming bipartisan majorities. Fast-forward to today: Merrick Garland never even received a vote. Democrats sought to filibuster Neil Gorsuch’s nomination, so Republicans eliminated it—just as Democrats had done to fill the D.C. Circuit with President Obama’s nominees. It is doubtful whether any Supreme Court nominee in the foreseeable future will be confirmed when the White House and Senate are in opposite hands. (Perhaps not coincidentally, Justice Kennedy was the last one to be confirmed in that situation.)

The animosity has trickled down to the circuit court level, where confirmation votes have become increasingly party-line affairs. Perversely, the most qualified nominees often attract the strongest opposition, since they are seen as potential future Supreme Court picks. Just ask Gibson Dunn partner Miguel Estrada, whose nomination to the D.C. Circuit Democrats blocked, or California Supreme Court Justice Goodwin Liu, whose Ninth Circuit nomination suffered the same fate at the hands of the GOP.

It is easy to lament this state of affairs; it is harder to say what can be done about it. While contemporary judicial politics may be unseemly, demeaning, and nasty, they are not irrational. Politicians, voters, and advocacy groups have made judicial nominations into scorched-earth battles because they rightly perceive that much is at stake. More and more high-profile questions of public policy are resolved at the constitutional level by the Supreme Court, cementing certain outcomes into place for decades. In a democracy, the people will have their say one way or another. If they can’t do it by electing representatives, they will do it by demanding their representatives ensure the nomination and confirmation of like-minded Justices.

It is easy to lament this state of affairs; it is harder to say what can be done about it. While contemporary judicial politics may be unseemly, demeaning, and nasty, they are not irrational. Politicians, voters, and advocacy groups have made judicial nominations into scorched-earth battles because they rightly perceive that much is at stake. More and more high-profile questions of public policy are resolved at the constitutional level by the Supreme Court, cementing certain outcomes into place for decades. In a democracy, the people will have their say one way or another. If they can’t do it by electing representatives, they will do it by demanding their representatives ensure the nomination and confirmation of like-minded Justices.

Ask conservative legal advocacy groups why they care so much about the Court, and you are likely to hear about overturning Roe v. Wade, preserving and extending Second Amendment rights, and ending affirmative action. Ask liberal groups the same question, and you are likely to hear about protecting Roe, overturning Citizens United and Heller, ending capital punishment, and promoting LGBT rights. To be sure, these are not the only reasons people care about the Supreme Court, but they are all near the top of the list—and collectively, they account for the lion’s share of the intense energy surrounding judicial confirmation battles.

What do these things have in common? They all involve areas in which the Supreme Court has interpreted, or is being asked to interpret, the Constitution in a way that prevents one side or the other from achieving important policy goals through the normal legislative process. The Court then becomes more important than legislation. If the Court is effectively settling major policy disputes through constitutional interpretation, ordinary people are going to care a lot about who sits on the Court.

Viewed in this way, the consensus confirmations of Justices Scalia and Ginsburg were an unsustainable vestige of an earlier era in which—partly because the two parties themselves were ideologically diverse—the Supreme Court rarely engaged in constitutional interpretation in a way that clearly favored the policy goals of one side or the other. Political norms often lag behind on-the-ground reality, but the politics of judicial confirmation have now fully adapted to the modern era.

To be clear, this is not to suggest the Justices are attempting to enact their own policy preferences into law. There is no reason to believe that any Justice in recent times has generally done anything other than follow his or her own sincere understanding of what the Constitution means. But it turns out that the constitutional views of Justices tend to overlap—not perfectly, but to a very large extent—with the policy preferences of the political coalition that shepherded them into office. That is not surprising, given the overwhelming incentives that presidents and senators have to pick Justices who will please their voters. In light of the far-reaching disagreements Americans have over what many constitutional provisions mean, faithful adherence to “the Constitution,” on its own, is not a formula for calming the wars over the federal judiciary. It’s what gotten us to where we are.

The Supreme Court Prisoner’s Dilemma

So what is to be done? One possibility is simply to embrace, or at least accept, the current situation as the new normal—an inevitable consequence of the Court doing its job in today’s political climate. A second option is to search for some way to reduce the Court’s involvement in high-stakes political disputes, even if it means forgoing landmark constitutional rulings. The only alternative to the path we are currently on is a renewed, shared, principled commitment to judicial restraint.

Some, understandably, will prefer the first option. People who feel strongly that the judiciary must protect certain liberties—abortion or gun rights, say—surely will view it as an abdication of the Court’s role to step back simply because some of its rulings prove controversial. They may be willing to live with a sharply polarized confirmation process, and also willing to run the risk that the other side will manage to enact some of its own policy goals into the Constitution. Libertarian types might even like it when the Court intervenes aggressively to protect rights against democratic encroachment from both the right and the left.

These views are coherent and defensible ones, but they are highly problematic. Think about the practical implications if politics come to revolve around the Supreme Court, some of which are already upon us. No one could ever in good conscience support an opposing party’s presidential candidate—no matter how unqualified, corrupt, or racist their own party’s candidate—lest they risk ceding the commanding heights of the federal judiciary to the opposition. The most consequential decisions in American life would turn on the health and well-being of particular 80-plus-year-old lawyers. The temptation to resort to increasingly extreme measures, like court-packing, will only grow stronger.

For these reasons and others, many people might prefer a Court that is more deferential to democratic outcomes—but only if the other side goes along too. This is a classic prisoner’s dilemma: we would be better off if we could agree to limit the Court’s involvement in politically charged disputes, but neither judicial liberals nor judicial conservatives are willing to disarm unilaterally.

In theory, this prisoner’s dilemma could be solved through the political process. The President and Senate could insist on judicial nominees who will exhibit greater deference to legislatures, or could seek to require a supermajority vote on the Court to invalidate statutes on constitutional grounds. But the prevailing partisan animosity and mistrust make this a remote prospect, to say the least. In all likelihood, if there is to be a concerted effort for the Court to take a step back, it will have to originate with the Justices themselves.

That may not be likely, but it isn’t impossible. Among all American political institutions, the Supreme Court is uniquely well designed to overcome a prisoner’s dilemma. It’s an extreme repeat-play institution: there are only nine Justices, who enjoy life tenure, serve for decades, and work together closely on dozens of cases each year—giving them an unparalleled opportunity to build trust. Not only that, but the Justices give detailed explanations (in the form of opinions) for resolving cases the way they do, which can serve to bind them to resolve future cases in accordance with previously articulated principles. If there were a cross-ideological group of four or five Justices willing to place the institutional interests of the Court ahead of their own constitutional views, together they could lead the Court down a more deferential path.

That may not be likely, but it isn’t impossible. Among all American political institutions, the Supreme Court is uniquely well designed to overcome a prisoner’s dilemma. It’s an extreme repeat-play institution: there are only nine Justices, who enjoy life tenure, serve for decades, and work together closely on dozens of cases each year—giving them an unparalleled opportunity to build trust. Not only that, but the Justices give detailed explanations (in the form of opinions) for resolving cases the way they do, which can serve to bind them to resolve future cases in accordance with previously articulated principles. If there were a cross-ideological group of four or five Justices willing to place the institutional interests of the Court ahead of their own constitutional views, together they could lead the Court down a more deferential path.

This idea is not new. In fact, it bears a striking resemblance to the way Chief Justice Roberts has described his vision for the Court. As he put it, “judicial temperament is a willingness to step back from your own committed views of the correct jurisprudential approach and evaluate those views in terms of your role as a judge.” A decade later, it is fair to say the Chief Justice has achieved limited success at best in that effort. Apart from his own courageous and underappreciated vote to save the Affordable Care Act from being struck down in 2012, there have been few prominent examples of Justices voting against their own ideological tendencies in an effort to find consensus in favor of judicial restraint in high-profile constitutional cases.

Some of the Chief Justice’s critics have taken that as evidence that his own professed commitment to restraint is disingenuous. A more charitable explanation is that he has not been able to find partners to join him and he is unwilling to go it alone. As Roberts himself has recognized, at the end of the day, “a chief justice has the same vote that everyone else has.” Justice Kennedy is temperamentally moderate and has a unique mix of views, but is no devotee of judicial restraint. Justice Scalia was an intellectual giant, but had limited interest in forging compromise if it meant watering down his core beliefs. Justice Breyer is a pragmatist and is sometimes a consensus-builder, but has not usually been willing to distance himself from the Court’s liberal bloc in major constitutional cases.

A principled commitment to restraint in constitutional interpretation is painful. For conservatives, it means forgoing judicial efforts to end race-based affirmative action or gun control, or rein in the administrative state. For liberals, it means giving up on decades-old dreams of the Court abolishing the death penalty or recognizing affirmative constitutional rights in areas like education. It also means beginning to come to grips with the reality that Roe v. Wade, even on its own terms, has been a failure. Unlike other landmark constitutional rulings like Brown v. Board of Education or the reapportionment cases of the 1960s that established the “one person, one vote” principle, Roe has not attained the near-universal popular acceptance necessary to cement it into American law. All it has done was to move the passionate debate about abortion rights from the realm of normal democratic politics to the realm of judicial politics—with corrosive effects on both.

The Court’s Legitimacy in the Trump Era and Beyond

At first blush, Donald Trump’s presidency might seem like an odd time to call for a renewed commitment to judicial restraint. But for the Court to be an effective check on an overreaching executive branch, it must preserve its legitimacy as an institution, which in turn demands that the Court avoid being seen (as it increasingly is) as just another political actor in a dysfunctional Washington.

There is a reason why Alexander Hamilton described the judiciary as the “least dangerous” branch of government. The Supreme Court has no guns or tanks, nor any revenue other than what Congress sees fit to give it. It has only one source of power: the legitimacy that its decisions have in the eyes of the public. And every high-profile, 5-4 decision split along ideological lines gives away a little bit more of that legitimacy. So does every titanic political clash over a nomination. As Chief Justice Roberts put it in 2007, “what the Court’s been doing over the past thirty years has been eroding, to some extent, the capital that [John] Marshall built up.” Since then, the situation has gotten worse, not better.

President Trump has made it clear that he has no qualms about attacking the federal judiciary when it stands in his way. It is not hard to imagine he might be tempted to ignore unfavorable rulings. Whether he (or a future president) can do so depends on restoring the Court to its limited, but critical, role in our democracy. All of us—citizens, politicians, lawyers, judges, and the media—have a role to play in that effort. But its success or failure is likely to depend, ultimately, on the choices the Justices themselves make.

Josh Patashnik is an associate at Munger, Tolles & Olson and clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy during October Term 2012. Views expressed in this article are his own, and not those of Munger, Tolles & Olson or any of the firm’s clients.

Notes:

- https://newrepublic.com/article/104898/john-roberts-supreme-court-aca

- https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2007/01/robertss-rules/305559/

- https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2007/01/robertss-rules/305559/