Eight Steps to Happiness and Effectiveness

Practicing law is powerful, and practicing mindfulness is a powerful addition your legal toolbox. It’s like having a superpower: you’re the one who can bring calm, focus, and wisdom to even the most explosive situations, with a minimum of stress.

That’s because when you practice mindfulness, you are aware of how the mind works. You are no longer trapped by reactivity. You develop positive, productive habits. Few tools are as important as mindfulness to your effectiveness and wellbeing.

So what is mindfulness? It’s not about telling your assistant to be mindful to file the motion. It’s the ongoing practice of present moment awareness, even when things are difficult. It contains an ethical component, and it requires some work.

So what is mindfulness? It’s not about telling your assistant to be mindful to file the motion. It’s the ongoing practice of present moment awareness, even when things are difficult. It contains an ethical component, and it requires some work.

Legend has it that mindfulness began 2,600 years ago in India, with Siddhartha Gautama, later known as the Buddha. Exploring the intricacies of the human mind, Siddhartha figured out some things about life:

The first thing is that life is full of problems, which is also certainly true of the practice of law.

But the second thing is that the problem isn’t the problems; the problem is the untrained mind. Persistent worry, rumination, avoidance, resentment, and anxiety arise and stick because the mind is not trained in present moment awareness. In the absence of such training, the mind defaults to a common human state: wanting things to be different than they actually are.

This ‘wanting’ falls into four categories:

- Wanting something you don’t have in the moment (a bigger book of clients, more time with your kids

- Not wanting something you do have in the moment (a difficult colleague, a bum knee)

- Wanting to become something you’re not, yet (a partner, a better friend)

- Wanting to be less of something, right then (anxious, depressed)

The good news, and the third thing Siddhartha figured out, is that you can train your mind in present moment awareness: to want and not-want much less, and instead to be calm, focused, and positive, no matter what is happening.

There are eight steps to this training:

There are eight steps to this training:

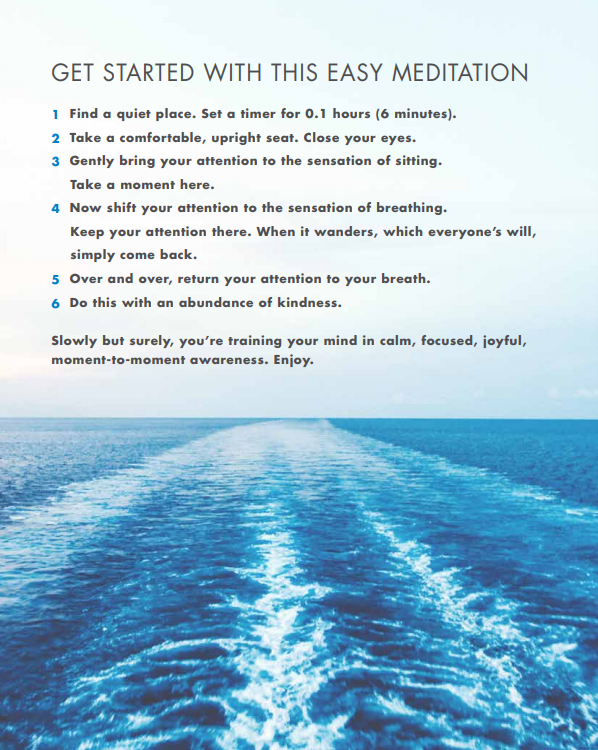

One: learn mindfulness meditation. It’s simple and rewarding. Because of its tendency to stabilize and focus the mind, it actually gives back much more time than it takes. It provides insight into how your mind is working in the moment, so you don’t walk into a meeting unaware that anger is driving you. And it provides you with a laboratory in which to try out various new states of mind like patience, attunement, and self-compassion.

Two: put some effort into your meditation practice. Meditate six or twelve minutes a day to start – that’s just 0.1 or 0.2 hours, respectively. Over time, you will develop a calmer, steadier, more focused mind, and the ability to employ intentional states like patience, not in a theoretical sense, but on the ground, in the moment, when you need them the most.

And you will realize that although your job is to think things through, you don’t have to believe every thought you have. For example, right now you may be thinking you don’t have six or twelve minutes to spend meditating. Challenge that thought. You probably spend more time than that shopping on Amazon. Contemplative neuroscience confirms that if you meditate instead, you can literally change your mind. Isn’t that better than a new pair of shoes?

Three: relax while you are meditating. Breathe, settle in, shift away from thinking and worry, and you will experience what you already knew: that a relaxed mind is better able to concentrate than a stressed mind. Once you manage that shift a few times, you will be able to relax your mind on demand, when you need it the most, in the present (stressful) moment.

Four, Five, and Six: be mindful of the things you say, do, and work on.

Meditation is solitary mindfulness practice. You may meditate with others, which is a great support, but meditation is fundamentally a solitary investigation.

Being mindful in everyday life is the portable aspect, and occurs when you are interacting with others. Sometimes, portable mindfulness arises as a result of solitary mindfulness. For example, if you notice while meditating that the thought of an aggressive colleague makes you tense and anxious, you can practice relaxing when that thought arises. Repeating that practice actually carves new neural connections in your mind, making it very likely that, over time, you will relax automatically when you see your colleague.

In addition, portable practice is also about following a set of ethical guidelines for communicating, going about your day, and working. For example, mindful communication is not saying, writing, or posting anything false, malicious, harsh, or gossipy. Try that today and you will probably feel pretty great tonight, knowing you have been truthful, kind, and thoughtful all day.

Mindful communication also offers a solution for delivering bad news. Delivering bad news mindfully means delivering it at a thoughtful time, truthfully, gently, and as a benefit rather than an insult. It changes the dynamic entirely in difficult conversations with clients, staff, colleagues, and even your family.

Mindful legal work is work that causes no unnecessary harm. Physicians take the Hippocratic oath, which includes the promise to abstain from all harm. You probably can’t do that: your job is to win, and the loser often feels harmed. But there is no need for unnecessary harm.

To discern whether or not your work is causing unnecessary harm, try this:

Before saying, doing, or working on anything, reflect on whether you might cause unnecessary harm. If so, find another way forward.

While saying, doing, or working on anything, periodically reflect on whether you’re causing unnecessary harm at the time. If so, stop and find a less harmful path.

After speaking, acting, or working on something, reflect. If you’ve caused unnecessary harm, apologize and find ways to avoid doing that in the future.

Mindfulness is not the practice of perfection. As you learn and put effort into mindful communication, action, and work, you will notice how often you fail. But failing is not only unavoidable, it is also good news.

Every time you notice you have been unmindful, you have the opportunity to try again. As you do that over and over, and especially if you do it without self-recrimination, you will become more and more mindful: more focused, calmer, more effective, and happier.

There are two final steps to becoming a mindful lawyer.

The seventh step in the training is to understand that what goes around, comes around. This is relatively simple: When you speak or act harshly, you will receive a like-kind reply. If you are thoughtful and ethical, you will be known as a great lawyer.

The seventh step in the training is to understand that what goes around, comes around. This is relatively simple: When you speak or act harshly, you will receive a like-kind reply. If you are thoughtful and ethical, you will be known as a great lawyer.

Intention is the eighth and final step in the training. Intentions drive you, whether you realize it or not. Becoming aware of your intentions is therefore critical: when you know what they are, you know what is driving you. And when you set your intentions, you have a good chance of achieving them. The classical intentions of mindfulness are to give up ill will, be kind, and cause no harm. If you are not sure where to start, start there.

The benefits of mindfulness are obvious and compelling. And they are sorely needed in the law. In August 2017, the National Task Force on Lawyer Wellbeing, a coalition of ABA commissions and divisions, the National Conference of Chief Justices, and others, published The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change . The report named what has been known for a while: that anxiety, depression, substance use, chronic stress, and suicide are rampant in the law, and that we need solutions. And mindfulness meditation was named as one of the top solutions to these urgent, devastating problems.

Motivated by the pain and suffering of his times, Siddhartha taught the eight steps of mindfulness as a powerful cure for problems like the ones lawyers experience, and to cultivate effectiveness, wellbeing, and happiness. Those eight steps are as crucial today as they were 2,600 years ago, and amount to a superpower addition to your legal toolbox. In fact, nominated or not, if you practice mindful lawyering, you probably qualify as a real Super Lawyer to your clients, staff, colleagues, friends, and even your family.

Judi Cohen is a lecturer at Berkeley Law and the founder of Warrior One, which offers mindfulness training for the legal mind. She is also a founding board member and chair of the Teachers Division of the Mindfulness in Law Society.

The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change. The Report of the National Taskforce on Lawyer Well-Being. 2017. Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/images/abanews/ThePathToLawyerWellBeingReportRevFINAL.pdf