Every day, in countless rooms and Zooms, court reporters encounter situations like these true stories:

- As she walked into the conference room, the noticing attorney looked her over and remarked in front of everyone present, “Guess I got the short straw today.”

- Six lawyers at a deposition agreed to work through lunch. The noticing attorney’s secretary walked around the room and took everyone’s orders – except the court reporter’s, who presumably did not need to eat, take a break, or use the facilities.

- The questioning attorney kept interrupting the witness and opposing counsel’s objections. The reporter asked him repeatedly to please slow down and not interrupt other speakers. He ridiculed her, and she took a break. Later, opposing counsel said, “I would like to state for the record that in my 36 years of litigation practice I have never seen a court reporter treated as rudely and unprofessionally by an attorney as Mr. Jones did this morning.”

The above behaviors are shocking and smack of rankism, especially in this age of #MeToo and increased social consciousness.

In June 2014, the federal courts of the Northern District of California implemented Guidelines for Professional Conduct. (1)

“Lawyers owe a duty of professionalism to their clients, opposing parties and their clients, the courts, and the public as a whole. Those duties include, among others: civility, professional integrity, personal dignity, candor, diligence, respect, courtesy, cooperation and competence.”

Yet the Guidelines provide no mention of a “duty of professionalism” nor “duty” of civility, respect, courtesy, and consideration for the highly skilled, intelligent legal professionals whose duty is to capture and protect the record lawyers are making.

This troubling pattern of disrespect likely originated on TV, the biggest influencer of belief systems before the internet.

Stenographers have been depicted pecking on weird-looking machines with overflowing paper trays (even recently in Episode 4 of SVU’s S22), (2) and they don’t speak except when asked to read back.

These subliminal images broadcast over decades have resulted in viewers believing the unspoken “story” that reporters are inept and must be silent.

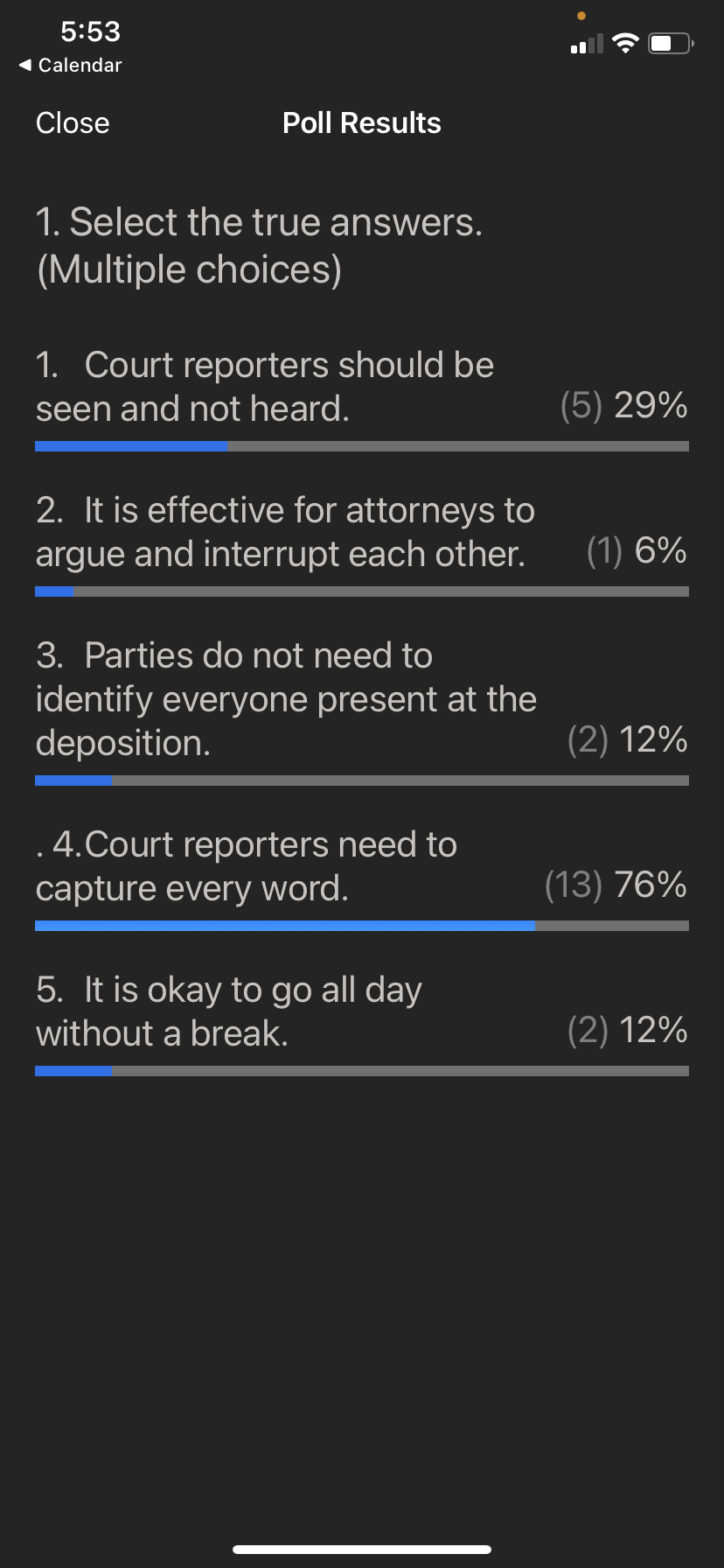

In the attached poll, I asked law students last spring to select all the true answers of five statements. 29% chose “#1: Court reporters should be seen and not heard.” (3) The only correct answer is #4.

As I wrote in my BASF 2020 article, Silent No More: Court Reporters Speak Up for the Record, (4) the Court Reporters Board of California requires court reporters to interrupt proceedings:

“The fundamental duty of a court reporter is to protect the record, including interrupting if the accuracy of the record is jeopardized.” (5)

No court reporter wants to interrupt attorneys’ questioning and momentarily stop proceedings, but as officers of the court and guardians of the record, they must in order to produce impartial and verbatim transcripts of proceedings.

The integrity of the record and your appeal are at risk if they don’t.

Save the Date:

Joanna Storey, Esq., and I will co-present a lunchtime CLE on September 15th tentatively titled Civility & Communication in a Hybrid World.

About the Author:

Ana Fatima Costa, a former RPR and California CSR, is a court reporter advocate, author, coach, and speaker.

Ana Fatima Costa, a former RPR and California CSR, is a court reporter advocate, author, coach, and speaker.

References

(1) USDC Northern District of CA, Guidelines for Professional Conduct

(2) TikTok message to Dick Wolf from Canadian Court Reporter Chelsey Fafard, @stenoholics

(3) Zoom poll created by author launched at a SF Bay Area law school

(4) Costa, Ana Fatima, Silent No More: Court Reporters Speak Up for the Record, Bar Association of San Francisco (Aug 2020)

(5) Best Practice Pointer #1: How to Interrupt Proceedings, Court Reporters Board of California