Oh, For It To Be 1985 Again!

The Bar Association of San Francisco in 1985

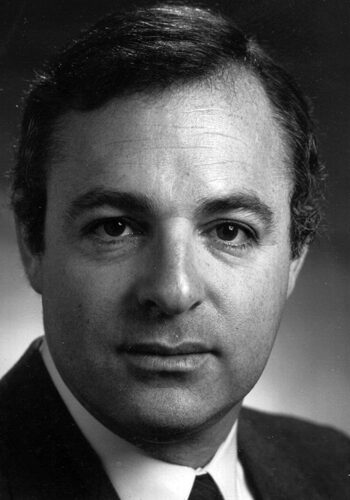

by Jerome B. Falk, Jr., 1985 BASF President

Most old guys asked to recall something that happened many years ago respond: “where did the years go?” I am no exception. And as for the answer to that question, I haven’t a clue. All I can tell you that more than 37 years ago I stood at the podium of the Hyatt Regency ballroom and told the assembled lawyers and friends that as BASF’s new President, I would lead the Association to support the retention of Chief Justice Rose Bird, Justice Joe Grodin and Justice Cruz Reynoso against a campaign to terminate their tenure on the Supreme Court of California.

But that is not the beginning of the story of my one year of service as President of the Association. Earlier that month, I chaired a three-person selection committee formed to screen applicants for Executive Director of BASF. We had an embarrassment of riches, but settled on Professor Drucilla Ramey, a distinguished member of the Golden Gate University School of Law faculty. I had known Dru for many years, having served with her as an officer of the ACLU of Northern California when she was Chair of its Board of Directors. Our deliberations were a riot: our committee agreed that we would not discuss the candidates until we had interviewed all of them, and then only as we plowed through the list during our post-interview conference. With three names to go, it suddenly became obvious to me that, without the merest mention of her name, my two colleagues and I all favored Dru’s selection. And, indeed, I had read my colleagues' facial expressions and body language correctly. So, sadly, we agreed to recommend her selection to the BASF Board without even pausing to discuss her many qualifications and virtues!

A few days later, we presented our unanimous recommendation to the Board of Directors, which quickly agreed. One director—our most conservative member—looked as if he had just swallowed a glass of hemlock. But within a few months, he had become a huge fan of Dru’s and very glad that he had kept his profound doubts to himself. It’s really neither cliché nor overstatement to say that any success I, or my successor Presidents, may have had in leading BASF was due in substantial part to Dru’s energy, imagination, commitment and talent. She knew where the Bar Association needed to go, and with each successive President and set of officers she gently but determinedly steered all of them in the right direction.

There was no doubt that BASF would have to support the Chief Justice and her two colleagues in the Retention Election. The California Constitution doesn’t subject appellate judges to direct elections at which others may run; instead, voters are asked whether Justice so-and-so should be retained for another term of office. In the past, voters agreed to retain Supreme Court and Court of Appeal Justices by large margins. But 1986 was shaping up to be a battle royal for these three incumbent Supreme Court Justices.

The Chief Justice was the focal point of those who wanted these three Justices removed. She was said to be too liberal, especially in criminal cases and most especially in capital cases in which she had never voted to sustain a death sentence. And she had been accused—wrongly—of having delayed an unpopular decision until after her initial confirmation election. Although the Commission on Judicial Performance concluded, after public and private hearings, that there had been no wrongdoing (full disclosure: I was counsel for the Chief in that proceeding), many members of the public undoubtedly harbored doubts about the Chief and her Court from that episode.

Politically, the Bar had a tough sell. Due to numerous and recent decisions of the United States Supreme Court, and to decisions of the California Supreme Court as well, death penalty law was in a state of flux and many judgments of death were entered under rules subsequently declared unconstitutional. Those judgments had to be reversed, and in the process the Bird Court seemed to many members of the public to be engaged in a process of nullifying California law establishing a death penalty.

The difficulty of defending the three Justices and promoting their retention for another term was compounded by the lack of any agreed standard for retention or dismissal in the California Constitution. When voting for candidates for any office in the political branches, the issue for most voters is “which candidate do you like best”? And whether voters base their decision on the candidates' declared party, their economic policies, their likeability, or anything else is entirely up to those voters sole discretion.

The Bar’s position was that appellate judicial retention elections are—and necessarily have to be—different. Judges are not “representatives” as are members of the legislative and executive branches. They are not expected to decide cases according to popular will, but rather according to law. (Consequently, citizens do not “lobby” judges.) And sometimes judges must make decisions that are deeply unpopular; that is often the case when a judge or court declares a statute enacted in conformance with popular will to be unconstitutional. But that is precisely what we expected judges to be courageous enough to do. And if doing so could subject judges to the loss of their position (and livelihood), then there would potentially be a heavy thumb on the scale in every controversial case. The idolized goal of “blind justice” can’t fully function if judges know their judicial tenure could be cut short by an unpopular but correct decision.

In deciding to support retention of the three Supreme Court justices whose name would be on the ballot in 1986, we hoped to explain to our fellow citizens that judges are not making “political” decisions in accordance with the views of the electorate on the case before them, and that the proper question to ask in a retention election is merely whether the judge has done his or her job conscientiously and refrained from any misconduct. Now that position is not an easy sell to a citizenry accustomed to voting for the best candidate, and against candidates they don’t like. But that was the message BASF set out to convey.

I wish I could say that we were successful. But perhaps we did contribute to a greater understanding of the role of our judicial branch: that the judge’s obligation is not to decide cases according to the electorate’s will but rather to an honest interpretation of the law and the facts of the case. In any event, our worst fears that the defeat of these three Supreme Court Justices would lead to many electoral challenges at the trial court level and opposition to appellate justice retention does not seem to have come to pass.

My crystal ball is cloudy, but I hope that the vote against retention of Chief Justice Bird, Justice Reynoso and Justice Cruz was a one-of-a-kind event. I can say, with considerable relief, that in all my years of practice—years in which I argued many politically “unpopular” causes—I never once felt that the court’s fear of being removed from office as a result of an unpopular decision played the slightest role. For lawyers and litigants to come, may it always be that way. In the 1986 election, BASF was on the wrong side of the vote count, but the right side of history.

And the very first significant act of the BASF Board in my year of serving as the President—the selection of Dru Ramey as our Executive Director—was a huge success. I’m not bragging—just ask any of the Presidents or any of the members of the Board of Directors in the years that followed.

Jerome B. Falk, Jr., 1985 BASF president

Join the celebration

Visit the History Archive

Throughout this year, we are adding historical documents and articles to the newly created history archive in our online documents library.

Share a Memory

We'd love to hear from you. If you have a story, article, or historical photo related to San Francisco legal history, we'd love to hear from you.