“State intervention in the lives of families, even when absolutely necessary, is a traumatic experience for children and parents alike.”[1] Indeed, “[t]here are hardly more consequential acts the government can take than deciding whether to remove a child from the home and terminate familial rights.”[2]

“State intervention in the lives of families, even when absolutely necessary, is a traumatic experience for children and parents alike.”[1] Indeed, “[t]here are hardly more consequential acts the government can take than deciding whether to remove a child from the home and terminate familial rights.”[2]

Two years ago the ACLU’s white paper report “System on the Brink” warned that California’s “crushing caseloads in the California Dependency Courts undermine the right to counsel, violate the law and put children and families at risk.” Statewide average caseloads are triple the American Bar Association’s (ABA) recommended caseload of one hundred per attorney, and while less wealthy states like Georgia and Arkansas meet the ABA guidelines, California is incredibly far behind on its legal obligations to families served in dependency court [3].

Although California has enacted complex and demanding statutory requirements for lawyers practicing in this highly specialized area of law—rarely taught in law school—to date, the state hasn’t provided sufficient funds to meet its statutory obligations. The shortfall is $88.2 million [4]. Importantly, $88.2 million is needed to bring caseloads down to 141 per attorney, not the ABA recommended caseload of 100.

The need is palpable to the judges presiding over these matters. In an unprecedented letter to Governor Jerry Brown last May, 150 Superior Court judges representing forty-one counties pleaded with him to meet this critical need. This year, California Supreme Court Chief Justice Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye argues, “[t]he need to adequately fund dependency counsel for this most vulnerable group of people cannot be overstated,” yet those close to the legislative process do not predict a meaningful increase in funding statewide, and more than half of the state’s counties, including San Francisco, will suffer significant cuts to their already underfunded programs [5].

Funding Shortage to San Francisco

Locally, San Francisco Supervisor Malia Cohen, who strongly believes the state must fund these mandated legal services, sponsored a resolution, unanimously approved by the Board of Supervisors, that urged the governor and legislature to meet this obligation; in addition, she introduced a resolution overwhelmingly approved by San Francisco’s Democratic County Central Committee (DCCC), similarly urging both branches of government to fund dependency counsel statewide.

San Francisco is currently funded by the state at only 71 percent of need,[6] but under a reallocation plan urged by the governor and adopted by the Judicial Council, San Francisco will suffer a cut of $1.2 million in fiscal year 2017–2018. The Bar Association of San Francisco (BASF), which oversees and assures quality representation for indigent families of the dependency court, in partnership with the Superior Court has repeatedly reached out to state decision makers, warning that cuts of this magnitude will dramatically reduce the quality of representation in San Francisco. Our currently experienced and therefore efficient and cost-effective attorneys will leave the practice and it will take many years—even with restored funding at a later date—to rebuild the quality of this program. In the meantime, the costs to families, the city, and the state will grow exponentially.

Why Are Experienced Counsel So Important?

Research has long demonstrated that “providing high quality legal representation to all parties at all stages of dependency proceedings is crucial to realizing . . . tenets of fairness and due process . . . [and] clearly linked to increased party engagement, improved case planning, expedited permanency and cost savings to state [and city] governments.”[7] Outcomes improve when parents and children are represented by trained, effective, and competent counsel. The cost-effectiveness of experienced counsel carrying reasonable caseloads cannot be overstated, because skilled advocates protect abused and neglected children, reduce unnecessary reentries into foster care, increase timeliness and durability of reunification when appropriate, reduce intergenerational abuse, and help keep San Francisco’s families together in the community where they can have access to services and family/community support.

Who Are the Families in San Francisco’s Dependency Court?

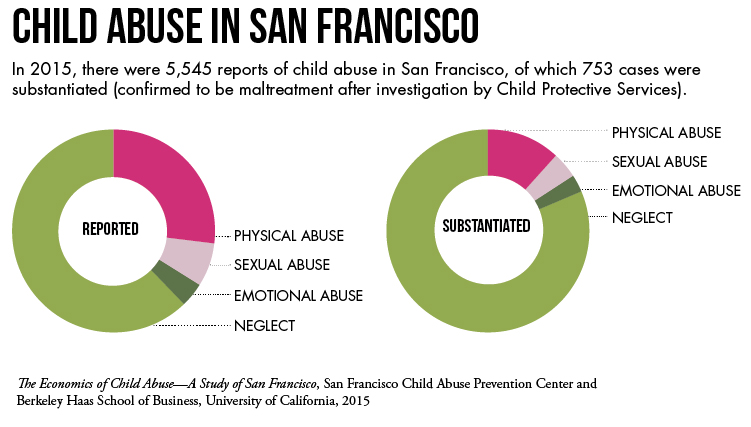

There are many assumptions about what brings a family into the dependency system. Last year, one in twenty-five children in San Francisco was involved in a case of alleged or suspected abuse. [8] Fourteen percent of suspected cases were confirmed: 81 percent of the cases involve neglect, 12.4 percent involve allegations of physical abuse, and just over 5 percent involve allegations of sexual or emotional abuse [9].

Most foster children have never experienced physical or mental abuse; rather the vast majority are removed from their homes because of risk of harm that is associated with living below the poverty level. As noted in a recent PBS NewsHour report, many of these families suffer from “toxic stress

. . . the result of poverty, abuse and neglect, domestic violence, just life’s circumstances when . . . a family lives under stress.” [10] And the stress of poverty changes the brain and one’s ability to cope: “When a person lives in poverty, a growing body of research suggests the limbic system [which processes emotions and triggers emotional responses] is constantly sending fear and stress messages to the prefrontal cortex, which overloads its ability to solve problems, set goals, and complete tasks in the most efficient ways.”[11]

And deeply troubling is the racial disparity. Fifty-six percent of children in foster care in San Francisco are African American/Black, ten times the percentage of San Francisco’s Black population; the percentage of Latino children in foster care is nearly double that of the city’s population.

This work is extremely challenging, legally and emotionally. Getting it right early in the proceedings is critical to the well-being of the child and family and less costly to the city and state. The economic burden on San Francisco of child maltreatment is $400,533 per child. [12]

While many families were interviewed for this article, four provide important examples of the staggering consequences of our dependency system and the importance of quality legal representation. In the following sections, a mother who nearly lost her only son, a foster youth who as an adult faced removal of her own children, and two foster parents who ultimately adopted children, share their stories. Dependency proceedings are closed and the records are sealed. Therefore the names of interviewees have been changed to protect the privacy of the children and parents who graciously shared their very painful stories with BASF.

Amara, A Mother

Amara was born and raised in West Africa; she became a US citizen and married, but her marriage was not to last. Separated from her husband, she found coparenting of their only child nearly impossible because the divorce was highly contentious; her former husband “just hated me and found it impossible not to hurt me.” This devoted mother found herself accused of something that never happened: taking inappropriate photographs of her son, and to her horror, her ex-husband’s accusations were believed. Child Protective Services (CPS) was called and the agency removed the child while the proceedings were pending; physical custody of Amara’s eight-year-old son was awarded to her ex-husband. For nearly three months, Amara was unable to see her son except in public places under supervision. She was devastated. She was not working, had no income, felt powerless and terrified.

Amara’s court-appointed attorney believed in her innocence, fighting the allegations with “great skill and dedication.” “It took so much work and so much strategy and the involvement of experts. . . . If I had all the money in the world, I could never repay her for what she did for me and my son. ”

As required by law, an attorney was also appointed to represent Amara’s son, and at first the attorney believed the accusations, but through the work of Amara’s attorney, both her son’s attorney and CPS realized a terrible mistake had been made. Indeed, at the conclusion of the case, the supervising social worker connected Amara to a nonprofit where she now works, supporting women’s mental health needs. Some of the women are fighting to regain custody of their children removed from the home by CPS. “I am humbled that I get to sit with these women, and I am of them; I am grateful that I am able to help them and to give back.”

When Amara was advised that the governor had previously vetoed and will likely again veto additional funding for dependency counsel and that San Francisco faces a $1.2 million cut to its already underfunded budget, she was stunned, “Do I need to walk from here to Sacramento? This cannot be permitted!” Amara knows that in less capable hands, this false accusation would have destroyed her and her son.

Jasmine, Foster Youth, Parent

Jasmine was a foster youth who bounced between foster homes in San Diego and Redding. The experience was a painful one and left many scars. She’s highly critical of the system, which she explains has no place or effective support for teens, especially those who act out. “Ninety percent of teens are going to run from their placements—to a pipeline to prison.”

At nineteen, while going to school and living in a homeless shelter, Jasmine gave birth to the first of her five children. She was not emotionally or financially equipped to provide the stability they needed and found herself in dependency proceedings and her children in foster care—the very system she felt had failed to support her.

Through the relentless advocacy of her court-appointed attorney, Jasmine has custody of all five of her children and now at the age of thirty-five will soon be completing her bachelor’s degree in psychology, to be followed by a master’s degree in social work, so that she can guide youth through a system “the way I had hoped I could have been guided, when I was young.” Her lawyer, Jasmine explains, made this possible. “She knew me and I trusted her. She knew me well enough, for example, to know that individual therapy would work for me and the recommended group therapy would not, and she reminded me again and again that she believed I could become the mother I needed to be. This was true of my children’s court-appointed counsel as well, who encouraged me and protected my kids; these attorneys were a team. I had so much to overcome but these lawyers are all about the children and they are pro-family,” working tirelessly. “My children will not grow up as I did; I’m good at helping not only my children, but others who need to discover ‘how else’ to handle what challenges them.” Without these lawyers, Jasmine readily admits, her success and that of her children would have been impossible.

Janice, Adoptive Parent

Janice is a foster parent. Born and raised in San Francisco’s Mission District and now residing in Sacramento, she has served as a foster parent since the 1980s and has worked with the Children’s Home Society. She adopted a foster daughter and is currently the foster parent of two young brothers, hoping to finalize their adoption by the time this article is published. Janice is part of a large extended African American family. “There are three hundred of us; most in our extended family are so wonderful, but some have struggled with huge problems, on occasion, bringing them to into the dependency system.” Janice’s adopted daughter and two younger boys in foster care are relatives.

Janice describes the attorney appointed to represent the two boys as a “complete blessing—there is no one in their lives like her, and they surely know that she is passionate about and dedicated to their well-being.” The older of the two boys suffered greatly, and by age four, when he came into foster care, “had witnessed and experienced things no one (including adults) should—violent deaths, sex acts, drug use; he even acted as a lookout for the police, sometimes at 3:00 a.m., making him suspicious of the police to this day. This little boy suffers from PTSD and has been diagnosed with ADHD.” But Janice explains, with therapy, love, and stability, he’s come a long way in three years, and “he is clearly a gifted student.” She fully intends to be the boys’ “forever family” so that they never need to hear that they “belong to the state of California” or that they are “wards of the court.”

Janice describes the dependency proceedings and adoption process as tremendously complicated and challenging, and while one or two social workers have been helpful, most have been extremely unhelpful, and “these boys do not trust anyone but their lawyer, who has been the one constant and positive professional.” Janice worries about cuts to these critical legal services for “it’s only going to cost more if we can’t find legal counsel like this to solve these complicated problems. These kids will simply enter the pipeline to prison in the absence of trained, passionate lawyers like this.”

Michelle, Adoptive Parent

Michelle, a public health nurse and her husband Ben, a manager at BART, had an eleven-year-old daughter but felt compelled to do what they could when they heard that the great-granddaughter of Michelle’s mother’s best friend was in foster care in San Francisco. One of BASF’s dependency panel attorneys was appointed to represent the child whose mother was incarcerated.

Although Michelle had been involved as a professional with some of the work of the dependency system and therefore was no novice, this was her first personal intersection with lawyers, social workers, and judges. “This attorney was the one constant person in our Beverly’s life; we saw so many different social workers, each one with a different approach, different protocols and rules, but this dedicated attorney provided stability within a system that proved extremely difficult to navigate—even for us as professionals.” In short, this attorney “saved Beverly’s life; I can’t rave about this attorney enough; she’s in there fighting for these children with know-how, care, and professionalism.” Michelle’s initial goal was to provide support and a connection for this girl, but the family fell in love with her. Once the bond was made and the legal path cleared, Michelle and her husband adopted Beverly, who is clearly loved and thriving with this remarkable family.

A Judicial Perspective

The San Francisco bench is deeply troubled by the cuts to dependency counsel. Judge Susan Breall relies on skilled, experienced counsel. “I’ve presided in the criminal and delinquency courts and, of course, I’ve observed outstanding lawyers in these courts, but the experience, expertise, and effectiveness of the dependency panel attorneys are remarkable and consistently excellent,” she says. “I appreciate the complexity of the law and the demands on these attorneys. Because they are so experienced, they ably provide the information and advocacy that permits the court to make informed decisions in these very consequential proceedings.”

As a state and city, we must provide qualified attorneys with reasonable caseloads to represent our families and children. We are not meeting the state’s mandate because the state is not funding it. Failure to provide effective counsel only costs more as our foster youth enter a pipeline to either prison or intergenerational neglect and abuse. Similarly, without experienced counsel skilled at guiding parents through a complex legal system, parents will fail to access services that will help them solve the problems that brought them into dependency court.

None of the families interviewed trust anyone but their lawyers, who are often called upon to deliver difficult messages. Clearly, continuity of qualified counsel is important to the success of our children and their families; legal representation of minors lasts until the child reaches adulthood or is reunified with the family or adopted. A cadre of passionate, dedicated San Francisco attorneys has done a great job with an underfunded budget, but if the projected cuts become a reality, San Francisco and its families will suffer unwanted, avoidable consequences that will take far too many years and dollars to rebuild.

A Call to Action: Your letters of support are needed. To find out how you can help, please contact Julie Traun at jtraun@sfbar.org. She will provide you with contact information for your elected officials and sample letters of support.

Julie Traun is a criminal defense attorney and the director of BASF’s Lawyer Referral and Information Service’s Court Program. She can be reached at jtraun@sfbar.org

Notes

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families; issuance date January 7, 2017; http://www.cssp.org/media-center/blog/text/LR.IM.Final.Clean.FINAL.pdf.

- Soaring Caseloads, Flat Funding Crush Dependency System; May 28, 2015; https://www.aclusocal.org/en/node/1925.

- https://www.aclusocal.org/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/DependencyCourtsWhitePaper-CA.pdf

- The Judicial Council allocation methodology calculates that $202.9 million is required in statewide funding; the current funding is $114.7 million. http://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/tcbac-20170413-materials.pdf.

- Funding for dependency counsel is allocated by the Judicial Council, which seeks only $22.4 million of the $88.2 million dollar need.

- Need is defined as “funding sufficient to bring caseloads to 141 [per] attorney.”

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families; issuance date January 7, 2017; http://www.cssp.org/media-center/blog/text/LR.IM.Final.Clean.FINAL.pdf.

- The Economics of Child Abuse, A Study of San Francisco, https://sfcapcorg.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/economicsofabuse_report_sfcapc1.pdf.

- The Economics of Child Abuse, A Study of San Francisco, https://sfcapcorg.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/economicsofabuse_report_sfcapc1.pdf.

- Heidi Heissenbuttel, CEO, Sewall Child Development Center, PBS NewsHour, “Making the Grade,” March 21, 2017, “Inclusive Wellness Center Is an Oasis for a Neighborhood Left Behind”; http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/inclusive-wellness-center-oasis-neighborhood-left-behind/.

- How Poverty Changes the Brain, The Atlantic, April 19, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/04/can-brain-science-pull-families-out-of-poverty/523479/.

- The Economics of Child Abuse, A Study of San Francisco, https://sfcapcorg.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/economicsofabuse_report_sfcapc1.pdf.